Panic to possibility: the evolution of moral panics

Panic to possibility: the evolution of moral panics

By Nicolas Cook, Associate Director and Ewan Marsden, Senior Researcher - September 9, 2025

It has probably crept into your life without you noticing. How you research a holiday. How you communicate with friends. How you interact with customer service. Artificial intelligence (AI) has become part of our lives. But it has also become part of our collective fears, and is the latest in a long line of moral panics about technological change.

A continuous cycle

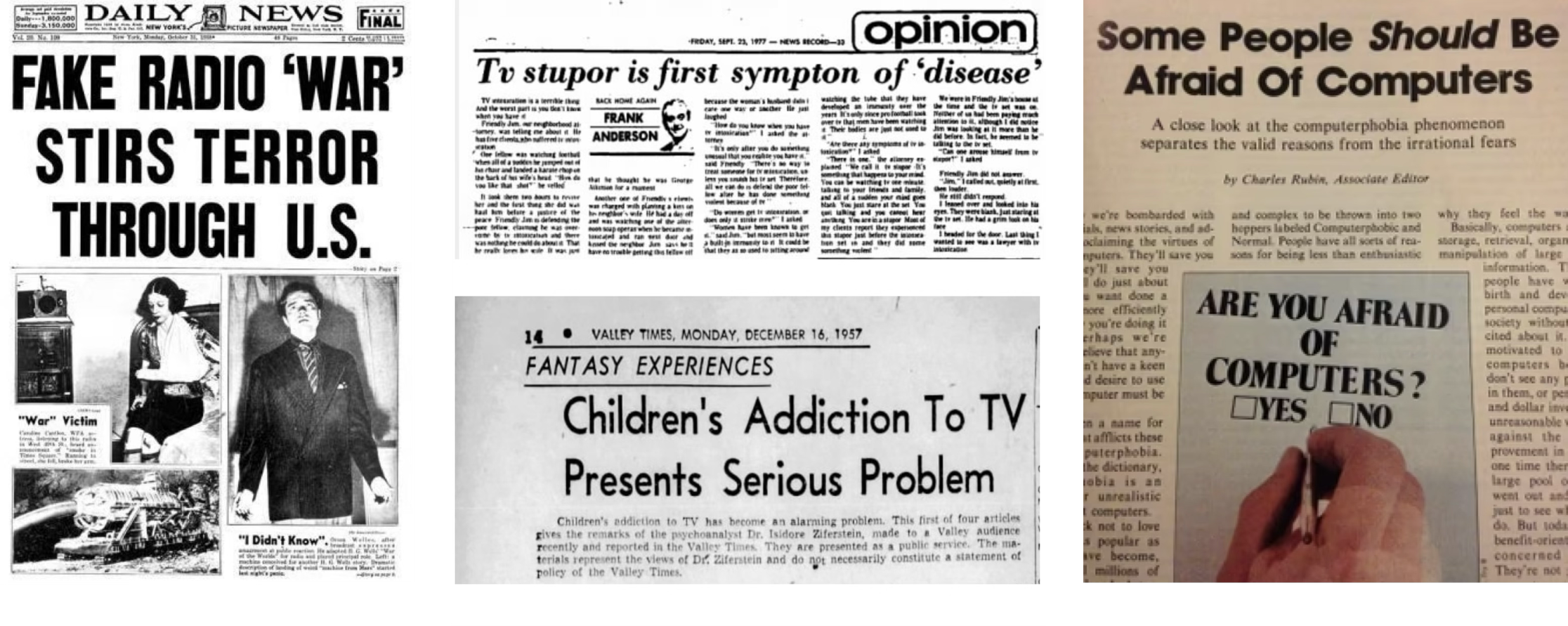

This is nothing new. For the past two centuries, technological innovation has often been accompanied by predictions of social collapse.

In the 1890s, people believed the telephone would disrupt family life and erode social order. In the 1920s and 1930s, people feared the radio would spread propaganda and corrupt society’s moral fibre. In the 1980s, computer technology adoption triggered widespread anxiety, including fears that]computers would replace humans entirely. What about the Millennial Bug? Widespread concern, and millions spent out of fear that computers would malfunction en masse at the turn of the new millennium.

Technological innovation is often greeted by a cycle of fascination and fear. And we are in one of these cycles again.

AI anxieties

AI is our latest collective fear, and one acutely felt by young people coming of age in what feel like uncertain times. The Good Side’s forthcoming study into attitudes and behaviours towards media and technological change describes how 66% of 16-24 year olds in the UK are concerned about the impact of AI on the world.

People want to know more, and public interest in AI has surged, reflected in increased search traffic and content creation across Google and social media. It is easy to understand why. In many aspects of daily life, we are seeing AI’s unlimited, disruptive power.

Or are we? Yes, AI is starting to change the way we do things, but mass disruption and seismic change is still a way off, and AI’s current social impact is potentially being overemphasised. For example:

- AI is being held responsible for a reduction in entry level jobs, although widespread economic uncertainty has been shown to be driving employers to pause hiring

- Schools and universities are fearful of AI’s misuse in academia, despite reported incidents still being low

- Online dating is being threatened by a rise in AI companions, though dating apps are still the most common way of meeting a partner

Industry hype and subsequent media attention have aided AI’s prevalence in dominant cultural narratives. But much of this is founded more on AI’s potential, opposed to current applications. This hype-cycle has been hugely beneficial to the tech sector. Since ChatGPT’s November 2022 launch, tech companies have experienced surging stock prices (Meta by over 500%, Alphabet by over 170%, Apple by over 60%). Current anxieties are not entirely based on what AI is doing now, but rather its as yet unrealised possibilities.

From panic to possibility

History tells us that moral panic does not need to lead to paralysis. At its best, it provides opportunities to innovate and explore new creative possibilities.

This moment is no different. Although AI innovation comes with some societal anxiety, people are also excited about its potential. Our study showed that 55% of 16-24s would like to know more about how to use AI in their daily lives, and 59% are using it more now than they were 12 months ago.

Past moral panics, and brand’s creative responses demonstrate how social problems can be transformed into opportunities to embed purpose and connection.

Radio as disseminator of propaganda to source of truth: Radio sparked concern over the spread of ‘immoral’ music, corrupt language, and propaganda, threatening social order. The UK launch of BBC Radio was an antidote to this: a regulated service providing news and entertainment to all.

TV as addictive entertainment to education tool: As televisions became a standard presence in homes, fears mounted over their “addictive” quality and the promotion of gratuitous violence and sexuality. America’s Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) saw this as an opportunity to use the ‘addictive qualities’ of TV for good and launched Sesame Street, educating children in their homes.

Computers as dehumanising to liberating: The rise of computers triggered widespread anxiety over the impact on individuals' health and wellbeing. Apple responded to this with their now infamous 1984 advertisement demonstrating how computers were not the route to disenfranchisement, but the route to liberation.

Looking ahead

Moral panics sparked by technological change reveal powerful insights about cultural fears. Many of these examples are ultimately rooted in evergreen fears around loss of control and connection, and the erosion of societal trust.

Brands that take this seriously don’t just protect themselves. They also generate increased relevance and resilience in changing times.

- Understanding the fear. Expressions of panic can signal what matters most to people. Listen carefully, and you’ll find the values worth defending.

- Engaging with empathy. Fear of AI is often fear of being left behind or dehumanised. Acknowledge these risks honestly, and show how you’re addressing them.

- Offering clarity and possibility. People don’t want empty reassurance; they want to see how technology can be used to elevate human needs, creativity, and imagination.

This is not about blind optimism, but responses grounded in deep human understanding. Brands that lean in with imagination, empathy and cultural intelligence will not just respond to new technological challenges, but they will help write the stories that culture lives by.